Overview

Peyronie’s (pay-roe-NEEZ) disease is a noncancerous condition resulting from fibrous scar tissue that develops on the penis and causes curved, painful erections. Penises vary in shape and size, and having a curved erection isn’t necessarily a cause for concern. But Peyronie’s disease causes a significant bend or pain in some men.

This can prevent you from having sex or might make it difficult to get or maintain an erection (erectile dysfunction). For many men, Peyronie’s disease also causes stress and anxiety. Penile shortening is another common concern.

Peyronie’s disease rarely goes away on its own. In most men with Peyronie’s disease, the condition will remain as is or worsen. Early treatment soon after developing the condition may keep it from getting worse or even improve symptoms. Even if you’ve had the condition for some time, treatment may help improve bothersome symptoms, such as pain, curvature and penile shortening.

Signs and Symptoms

Peyronie’s disease signs and symptoms might appear suddenly or develop gradually. The most common signs and symptoms include:

- Scar tissue. The scar tissue associated with Peyronie’s disease — called plaque but different from plaque that can build up in blood vessels — can be felt under the skin of the penis as flat lumps or a band of hard tissue.

- A significant bend to the penis. Your penis might curve upward or downward or bend to one side.

- Erection problems. Peyronie’s disease might cause problems getting or maintaining an erection (erectile dysfunction). But, often men report erectile dysfunction before the beginning of Peyronie’s disease symptoms.

- Shortening of the penis. Your penis might become shorter as a result of Peyronie’s disease.

- Pain. You might have penile pain, with or without an erection.

- Other penile deformity. In some men with Peyronie’s disease, the erect penis might have narrowing, indentations or even an hourglass-like appearance, with a tight, narrow band around the shaft.

The curvature and penile shortening associated with Peyronie’s disease might gradually worsen. At some point, however, the condition typically stabilises after three to 12 months or so.

Pain during erections usually improves within one to two years, but the scar tissue, penile shortening and curvature often remain. In some men, both the curvature and pain associated with Peyronie’s disease improve without treatment.

When to see a doctor

See your doctor as soon as possible after you notice signs or symptoms of Peyronie’s disease. Early treatment gives you the best chance to improve the condition — or prevent it from getting worse. If you’ve had the condition for some time, you may wish to see a doctor if the pain, curvature, length or other deformities bother you or your partner.

Causes

The cause of Peyronie’s disease isn’t completely understood, but a number of factors appear to be involved.

It’s thought Peyronie’s disease generally results from repeated injury to the penis. For example, the penis might be damaged during sex, athletic activity or as the result of an accident. However, most often, no specific trauma to the penis is recalled.

During the healing process after injury to the penis, scar tissue forms in a disorganised manner. This can lead to a nodule you can feel or development of curvature.

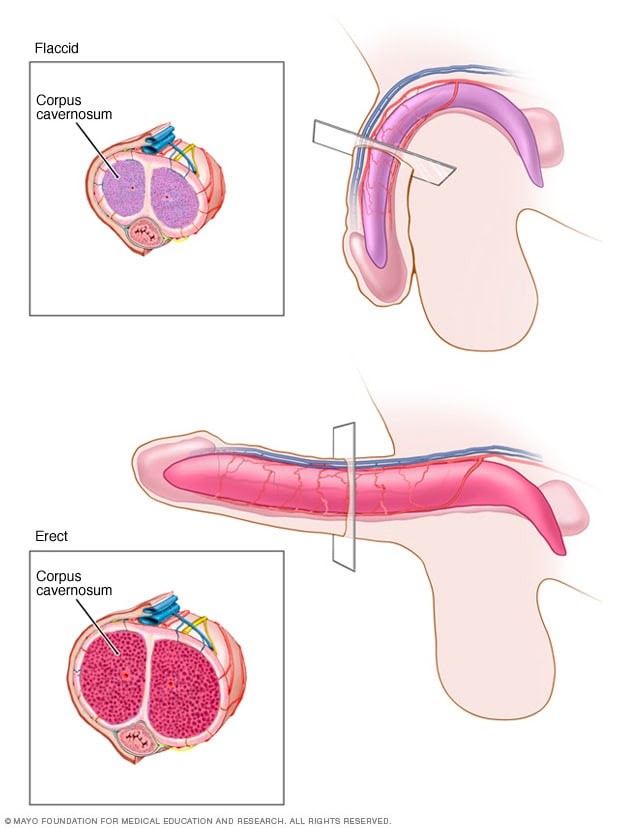

Each side of the penis contains a spongelike tube (corpus cavernosum) that contains many tiny blood vessels. Each of the corpora cavernosa is encased in a sheath of elastic tissue called the tunica albuginea (TOO-nih-kuh al-BYOO-JIN-e-uh), which stretches during an erection.

When you become sexually aroused, blood flow to these chambers increases. As the chambers fill with blood, the penis expands, straightens and stiffens into an erection.

In Peyronie’s disease, when the penis becomes erect, the region with the scar tissue doesn’t stretch, and the penis bends or becomes disfigured and possibly painful.

In some men, Peyronie’s disease comes on gradually and doesn’t seem to be related to an injury. Researchers are investigating whether Peyronie’s disease might be linked to an inherited trait or certain health conditions.

Risk factors

Minor injury to the penis doesn’t always lead to Peyronie’s disease. However, various factors can contribute to poor wound healing and scar tissue buildup that might play a role in Peyronie’s disease. These include:

- Heredity. If a family member has Peyronie’s disease, you have an increased risk of the condition.

- Connective tissue disorders. Men who have certain connective tissue disorders appear to have an increased risk of developing Peyronie’s disease. For example, a number of men who have Peyronie’s disease also have a cordlike thickening across the palm that causes the fingers to pull inward (Dupuytren’s contracture).

- Age. Peyronie’s disease can occur in men of any age, but the prevalence of the condition increases with age, especially for men in their 50s and 60s. Curvature in younger men is less often due to Peyronie’s disease and is more commonly called congenital penile curvature. A small amount of curvature in younger men is normal and not concerning.

Other factors — including certain health conditions, smoking and some types of prostate surgery — might be linked to Peyronie’s disease.

Complications

Complications of Peyronie’s disease might include:

- Inability to have sexual intercourse

- Difficulty achieving or maintaining an erection (erectile dysfunction)

- Anxiety or stress about sexual abilities or the appearance of your penis

- Stress on your relationship with your sexual partner

- Difficulty fathering a child, because intercourse is difficult or impossible

- Reduced penis length

- Penile pain

Treatment

Treatment recommendations for Peyronie’s disease depend on how long it’s been since you began having symptoms.

- Acute phase. You have penile pain or changes in curvature or length or a deformity of the penis. The acute phase happens early in the disease and may last only two to four weeks but sometimes lasts for up to a year or longer.

- Chronic phase. Your symptoms are stable, and you have no penile pain or changes in curvature, length or deformity of the penis. The chronic phase happens later in the disease and generally occurs around three to 12 months after symptoms begin.

For the acute phase of the disease, treatments range from:

- Recommended. When used early in the disease process, penile traction therapy prevents length loss and minimises the extent of curvature that occurs.

- Optional. Medical and injection therapies are optional in this phase, with some more effective than others.

- Not recommended. Surgery isn’t recommended until the disease stabilises, to avoid the need for repeat surgery.

For the chronic phase of the disease, several potential treatments are available. They may be done alone or in combination:

- Watchful waiting

- Injection treatments

- Traction therapy

- Surgery

This is where PRP has been used to help. Injections of Platelet rich plasma has demonstrated some early positive results with this difficult and challenging situation.